Research

Examples in Archaeology: The Multiple Burial in the Corner of the Hexamilion North of the Roman Bath (Gully Bastion)

When and where the feature was found

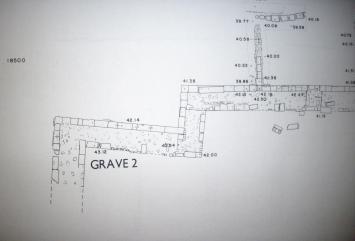

The multiple burial (Grave 2 Gully Bastion) is located in the Corner of the Hexamilion North of the Roman Bath at Isthmia. The grave cut into what is assumed to be ground level at the time of the construction of the Hexamilion wall which is a hard white soil. The grave itself was excavated in the 1970 season and was found under a later kiln or oven.

Gregory, T.E., Isthmia: Vol.5, The Hexamilion and the Fortress (1993)

Topelev = 41.08

Botelev = 40.18

Brief Description

Located in a corner of the Hexamilion wall the Gully Bastion Grave Two has the interior face of the wall forming both the West and the North sides with the North side slightly undercutting the Hexamilion by around 20cm. The sides of the grave are lined with large tiles, these tiles also included in their number one stamped tile[1] and another which being heavily smoke stained indicates that it may have originally been part of the nearby Roman Bath.[2] The interpretation of this tile as formerly of the Roman Bath is also suggested by how the smoke staining does not extend to the corners of the tile where it would have been resting on top of hypocausts.

The grave is actually split into two irregular sections, North and South. These two sections were split by a line of vertical tiles which ran West to East across the grave. Within the north section was found two skeletons with their heads to the west and within the south compartment eight skeletons were uncovered also with their heads to the west. There is some debate to who these individuals were, whether they were part of the garrison assigned to guard or build the Hexamilion or from some other associated part of society.

Underneath the lowest body in the southern section a number of artefacts were found, namely an Athenian glazed lamp fragment which shares much of the characteristics of other lamps found in the Roman Bath (IPL 70-100)[3] which can be dated to the second half of the fourth century after Christ. There is debate over the function of the lamp in the grave. Was it part of some religious ceremony for the deceased or simply just lost or for another reason yet to be thought of? Either way this lamp fragment allows for the best dating of the grave in relation to similar lamps found in the Roman Bath as mentioned previous. Several other items were found in the same area as the lamp fragment including a coarse dark reddish bowl (IPR 70-26) which like the lamp can be dated to the second half of the fourth century.[4] A bronze buckle (IM 70-32) and a bead on a wire (IM 70-54) were also excavated.

Interpretation:

The north side of the grave undercutting the Hexamilion along with the relation between the lamp fragment found in the south section of the grave in relation to lamps found in Roman Bath dating to the fourth century suggest that the grave was contemporary with the construction of the Hexamilion. This is further indicated by how the grave sides are the interior of the wall on two sides. The graves construction can hence be placed either at the time the Hexamilion was being built or slightly after but before the kiln/oven was placed on top.

The position of the skeletons within the grave suggests primarily a Christian burial with the skeleton’s heads to the west. Christian burials of the period were generally orientated East-West with the head to the West end of the grave in order to mirror the layout of the Christian Church and the direction from which Christ is meant to come on judgement day.

References

Gregory, T.E., Isthmia: Vol.5, The Hexamilion and the Fortress (1993), pp.42-45

Notebooks:

Gully Bastion 1970 Vol.2 – pp.47-72 May 1970

Gully Bastion 1970 Vol.3

Wohl ‘Deposit of Lamps’ No. 24

Fraser, P.M., Archaeology in Greece, 1970-71, Archaeological reports, No.17 (1970-71), p.9

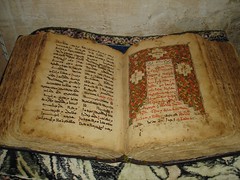

Philology: Introduction to the Significance of Language Analysis

When you first enter an ancient history or archaeology degree you are introduced to several sets of material evidence. Notably, the archaeology, material evidence, and philological evidence. But the philological side is more often than not rarely mentioned again. This is quite a shame considering some of the most interesting and revealing information comes from the ancient written sources. People generally fall into the trap of ignoring the writing in favour of the archaeology and artefacts and frankly you can’t really blame them because humans are naturally attracted to pretty visual things. I see this every day with the likes and shares on my Facebook page. But philology is all important too and if students can learn even a little about ancient writing and textual criticism, a whole new side to history and analysis opens up to them as it should.

Philology is derived from the Greek terms φίλος (love) and λόγος (word, reason) and literally means a ‘love of words’. It is the study of language in literary sources and is a combination of literary studies, history and linguistics. Philology is generally associated with Greek and Classical Latin, in which it is termed philologia. The study of philology originated in European Renaissance Humanism in regards to Classical Philology but this has since been combined to include in its definition the study of both European and non-European languages. The idea of philology has been carried through the Greek and Latin literature into the English language around the sixteenth century through the French term philologie meaning also a ‘love of literature’ from the same word roots.

Generally philology has a focus on historical development. It helps establish the authenticity of literary texts and their original form and with this the determination of their meaning. It is a branch of knowledge that deals with the structure, historical development and relationships of a language or languages. This makes it all the more significant to study as language is one of the main building blocks of civilisation.

There are several branches of philological studies that can also be undertaken:

Comparative philology is a branch of philology which analyses the relationship or correspondences between languages. For instance, the commonalities between Latin and Etruscan or further flung languages of Asian or African provinces. It uses pre-determined techniques to discover whether languages hold common ancestors or influences. It uses comparison of grammar and spelling which was first deemed useful in the 19th century and has developed ever since. The study of comparative philology was originally defined by Sir William Jones‘ discovery in 1786 that Sanskrit was related to Greek and German as well as Latin.

Cognitive philology studies written and oral texts in consideration of the human mental processes. It uses science to compare the results of research using psychological and artificial systems.

Decipherment is another branch of philology which looks at resurrecting dead languages and previously unread texts such as done and achieved by Jean-Francois Champollion in the decipherment of Hieroglyphs with the use of the Rosetta Stone. And more recently by Michael Ventris in the decipherment of Linear B. Decipherment would be key to the understanding of still little understood languages such as Linear A. Decipherment uses known languages, grammatical tools and vocabulary to find and apply comparisons within an unread text. By doing so more of the text can be read gradually as similarities and grammatical forms become better understood. The remaining text can then be filled in through further comparison, analysis, and elimination of incorrect solutions.

Textual philology editing is yet another branch of philology with includes the study of texts and their history in a sense including textual criticism. This branch was created in relation to the long traditions of Biblical studies; in particular with the variations of manuscripts. It looks at the authorship, date and provenance of the text to place it in its historical context and to produce ‘critical editions’ of the texts.

Significant Examples:

The importance of philology is exhibited in its use and achievements. Without philology the bible translation would be even more wrong, trust me read it in the original Greek. We would not be able to translate hieroglyphs, Linear B, Linear A, Sanskrit, any ancient language. Our entire written past would be blank, we would not have the information we have now on mathematics, social structure, philosophy, science, medicine, civilisation, transport, engineering, marketing, accounting, well anything really, knowledge would not have been rediscovered or passed on without the ability to study texts and language. Understand the love of words.

Related articles

- The unsung heroine who helped decode Crete’s ancient script (bbc.co.uk)

- Rediscovering Philology (sites.tufts.edu)

- The Open Philology Project and Humboldt Chair of Digital Humanities at Leipzig (sites.tufts.edu)

- Genes and Languages: Not So Strange Bedfellows? (23andme.com)

- Bavinck on Comparative Religion and Comparative Philology (calvinistinternational.com)

- How to Teach yourself Ancient (and Modern) Languages (graecomuse.wordpress.com)

- Welcome to GraecoMuse (graecomuse.wordpress.com)

- Alice Kober: Unsung heroine who helped decode Linear B (adafruit.com)

- The Unsolved Mysteries of the World (secretsofthefed.com)

- Macquarie Ancient Languages School – Winter Session (graecomuse.wordpress.com)

Antiochia ad Cragum: Archaeology Blog 2013

Only eleven days until travel and digging resumes for the 2013 season. This year we will be working on the agora it seems, shop complex and mosaic so you are bound to see lots of photos and interesting reports from this years season. So here is some background information on this amazing site where we will be digging and translating.

Excavations are currently being undertaken by the Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project headed by the University of Nebraska-Lincoln in the area of Rough Cilicia in modern Turkey.[1] The excavation site of Antiochia ad Cragum (Αντιόχεια Κράγου) is located about 8 miles to the East of the modern town of Gazipaşa, in the area of the village of Guney. Over the centuries, Antiochia ad Cragum has also been known by the names of Antiochetta and Antiochia Parva which basically translates to ‘little Antiochia’. The additional name ‘ad Cragum’ comes from the site’s position on the steep cliffs (Cragum) overlooking the Mediterranean coast in Southern Anatolia. The site covers an area of around three hectares and contains the remains of baths, market places, colonnaded streets with a gateway, an early Christian basilica, monumental tombs, a temple, and several unidentified buildings. The city itself was built on the sloping ground that comes down from the Taurus Mountain range which terminates at the shore creating steep cliffs; in some places several hundred metres high. The temple complex is situated on the highest point of the city and most of the building material remains though in a collapsed state. There is also evidence of a gymnasium complex nearby.

The harbour at Antiochia ad Cragum measures about 250,000m squared and is one of the few large, safe harbours along the coast East of Alanya.[2] On its Eastern side are two small coves suitable for one or two ships but with limited opportunity for shipping and fishing due to wave activities. The area is well situated as a defensible position against invaders. Recent terrestrial survey at Antiochia ad Cragum has had emphasis on finding evidence of pirate activity which has been limited, but it has turned up pottery principally from the Byzantine Period with additional pottery from the late Bronze Age, Hellenistic and Roman Periods.[3] Thirty stone weights and anchors have been uncovered, alongside lead stocks from wooden anchors and almost twenty iron anchors representing the early Roman through Ottoman periods.[4] There is little evidence of pre-Roman occupation at the fortress or pirate’s cove at Antiochia ad Cragum. Banana terracing may have caused much of the evidence to have been erased. The maritime survey has turned up shipping jars, transport amphoraes and anchors from the Byzantine, Roman and Hellenistic periods as well as a range of miscellaneous items. It is not possible to date the stone weights and anchors at present, but further research may assist in their analysis.[5] Many of them are small and likely to represent local fishing activities over a long period of time. The assemblage appears to indicate early activity to the West of the harbor moving East over time.[6] Access to the site these days is through the Guney village grave yard and past the old school house which is now used as the excavation’s artefact and equipment house.

History of the Site

The city of Antiochia ad Cragum was officially founded by Antiochis IV around 170 BC when he came to rule over Rough Cilicia. The site and its harbor likely served as one of the many havens for Cilician pirates along the South Anatolian coast, this is because of its small coves and hidden inlets. Unfortunately no definite pirate related artefacts or buildings are visible in the modern day. Antiochia ad Cragum’s pirate past ended with Pompey’s victory in the first century BC and the takeover of Antiochia IV. Initial occupation appears to have occurred in the Classical and Hellenistic periods, followed by a surge of activity in the Roman periods.[7] The area of Antiochia ad Cragum is also neighboured by a citadel on the Western peninsula which was built by Armenian princes and a well-preserved necropolis on the South-Eastern peninsula.

Pompey ended the pirate menace in 67 AD with a naval victory at nearby Korakesion, modern day Alanya. The emperor Gaius gave control of Rough Cilicia after this episode to the client king of Rome, Antiochis IV of Commagene around AD 38 and later in 41 AD under Claudius. After Pompey’s victory he founded and named Antiochia after himself but was removed by Vespasian in 72 AD. With this later change of control, Antiochia ad Cragum and the rest of Rough Cilicia fell under direct Roman rule as part of the enlarged Roman province of Cilicia. The numismatic evidence left at the site shows that there was a working mint at Antiochia for several centuries after the Roman takeover. One coin dates from 139-161 AD and reads of Marcus Aurelius as Caesar on the obverse with a nude male god holding a long sceptre and a mantle over his shoulder.[8] Other coins from Antiochia ad Cragum date from the mid-third century AD, with examples detailing Philip I and Trajan Decius.[9]

History of Excavations

The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project (ACARP) was founded by Professor Michael Hoff from the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, and Rhys Townsend from Clark University in 2005. ACARP started off as a facet of the regional survey, the Rough Cilicia Archaeological Survey Project (RCASP) which ran under the field direction of Nicholas Rauh of Purdue University. The aim of RCASP was to document and record the physical remains of the major cities and minor sites within the survey zone, this zone included the site of Antiochia ad Cragum. The members of the RCASP research team have already prepared and published a number of publications detailing the progress of the survey.

In the summer of 2005 Hoff and Townsend formed the separate project at Antiochia ad Cragum with the collaboration of architectural engineer Ece Erdoğmuş who is also from the University of Nebraska.[10] Originally the project at Antiochia ad Cragum began operating under the aegis of the local archaeological museum in Alanya. But in 2008 it was granted a full excavation permit by the Archaeological Directorate of the Turkish Ministry of Culture. Professor Hoff is a professor of Art History in the Department of Art and Art History at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where he has been since 1989. Hoff specializes in Greek and Roman archaeology. Townsend is a lecturer with the Department of Visual and Performing Arts in the Art History Program at Clark University.[11]

The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project has several goals which will hopefully be achieved in the next few years. The project will be pioneering in architectural and archaeological studies in Rough Cilicia. The main goal is the restoration of the temple to a sufficient point. The temple reconstruction is a huge work in progress as currently the project does not know how much of the architecture can be reused. This will not be determined until the marble blocked have been removed to the adjacent block fields, cleaned and repaired. After this has been achieved and the podium of the temple has been completely revealed and assessed, then the extent of the restoration can be determined and a full and detailed plan for restoration can be submitted to the Preservation Board of Historical Buildings in Antalya. This plan and its subsequent approval will be needed before final submission to the Ministry of Culture in Ankara for actual permission to carry out restoration.

The goals for the temple are shared by the local governmental authorities and the Ministry of Culture in a collaboration involving archaeologists, engineers, authorities and preservation officials. There is also a huge collaboration with the local villagers who reap many of the benefits of the excavations. They receive short-term employment opportunities as workers and guards on site and also long-term economic gain and education from the project. The site foreman who looks after the site year round is also a prominent member of the local community in the village of Guney and banana grower.

The first full season of digging at Antiochia ad Cragum began in 2005 and began by documenting the temple’s remains by surveying every block in situ with a total station. Two-hundred and seventy blocks were recorded which will be used to create an accurate plan of the blocks and their find spots. This allowed the researchers to determine the basic structure of the temple and some of the decoration and moulding that originally were associated into the structure. At this point, the dedicatee of the temple was unknown but bust remains suggest possibly Apollo or an Imperial personage. The 2005 season hypothesized that the temple belonged to the first half of the third century AD.[12]

The 2007 and 2008 seasons of the excavation saw a total of four-hundred and ten blocks catalogued, almost 50% of the material of the collapsed structure.[13] In 2008, the excavation team used Ground Penetrating Radar to survey for underground features. This first focused on the block field to make sure they were free of anomalies. The GPR unit was also used to survey the top of the temple platform and it indicated the presence of an intact arched vault underneath the stone platform. This chamber was already suspected because temples nearby at Selinus and Nephelion include the same form of feature. Additionally Professor Erdoğmuş began analysis of the block and lime mortar on site in order to gather authentic materials and assess the condition of the existing materials for the restoration process.[14]

The 2009 season saw the team continue the architectural block recording and removal as well as remote sensing and excavation. The architectural block removal focused on the western and southern quadrants of the collapsed temple with refined documentation and photographic techniques. The blocks were removed with the help of a local crane operator who became adept at carefully lifting the ancient material. By the end of the season there was three block fields being used and four-hundred and thirty-four blocks successfully moved and five-hundred and forty-six blocks catalogued with almost half drawn. This has left three sides of the temple cleared with the east side still to be cleared. GPR was also used to scan the suspected vaulted chamber. 2009 excavations of the deposits under the platform allowed further scans to be undertaken and further indication of the vaulted chamber. Fiberscopic Remote Inspection equipment was also utilized to investigate the original structural and architectural designs of the temple. Several cavities were investigated but unfortunately none allowed for deep probing.[15]

The excavations focused on the temple mound in 2009 starting with two small trenches (001 and 002) in the northern quadrant. Trench 001 revealed a long wall running parallel to the cella wall alongside the Eastern side of the temple podium. Much pottery and a frieze fragment was uncovered as well as a decorated columnar drum fragment. Trench 002 revealed little information concerning post-antique usage of the structure. Thick marble fragments of a floor were uncovered in both trenches 001 and 002. The suspected chamber vault’s entrance remained undiscovered after no evidence of an internal staircase was found. A trench 003 was also excavated to probe the exterior rear façade of the temple. Excavation through the fill around the temple revealed no discernible stratigraphy. Trench 003 also revealed the top of the base moulding of the temple supporting a large orthostate course.

Erdogmus, E., Buckley, C.M., and H.Brink, ‘The Temple of Antioch: A Study of Abroad Internship for Architectural Engineering Students’, AEI 2011: Building Integration Solutions: Proceedings of the 2011 Architectural Engineering National Conference, March 30 – April 2, 2011, (Oakland, 2011), 1-9

Hoff, M., “Interdisciplinary Assessment of a Roman Temple: Antiochia ad Kragos (Gazipasha, Turkey),” (with E. Erdogmus, R. Townsend, and S. Türkmen) in A. Görün, ed., Proceedings of the International Symposium on Studies on Historical Heritage, September 2007, Antalya, Turkey (Istanbul 2007) 163–70.

Hoff, M., “Bath Architecture of Western Rough Cilicia,” in Hoff and Townsend, eds. Rough Cilicia, New Historical and Archaeological Approaches. An International Symposium held at the University of Nebraska, October 2007 (Oxford 2011) 12 page ms; forthcoming.

Hoff, M., “Life in the Truck Lane: Urban Development in Western Rough Cilicia,” (with N. Rauh, R. Townsend, M. Dillon, M. Doyle, C. Ward, R. Rothaus, H. Caner, U. Akkemik, L. Wandsnider, S. Ozaner, and C. Dore) Jahreshefte des Österreichischen Archäologischen Institutes in Wien (JÖAI) 78 (2009) 169 page ms; forthcoming.

Hoff, M., “Rough Cilicia Archaeological Project: 2005 Season,” (with Rhys Townsend and Ece Erdogmus) 24. Arastirma Sonuçlari Toplantisi (24th Annual Archaeological Survey Symposium). Turkish Ministry of Culture (Ankara 2007) 231–44.

Hoff, M., “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2009 Season” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend), Anadolu Akdenizi Arkeoloji Haberleri (ANMED) 8 (2010) 9-13.

Hoff, M., “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2008 Season” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend), 27. Arastirma Sonuçlari Toplantisi (27th Annual Archaeological Survey Symposium).Turkish Ministry of Culture, Ankara 2009 (with R. Townsend and E. Erdogmus) 461-70.

Hoff, M., “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2008 Season” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend), Anadolu Akdenizi Arkeoloji Haberleri (ANMED) 7 (2009) 6-11.

Hoff, M., “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2007 Season” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend), 25. Arastirma Sonuçlari Toplantisi (25th Annual Archaeological Survey Symposium). Turkish Ministry of Culture (Ankara 2009) 95-102.

Hoff, M., “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2007 Season,” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend, S. Türkmen) Anadolu Akdenizi Arkeoloji Haberleri (ANMED) 6 (2008) 95-99.

Hoff, M., “The Rough Cilicia Archaeological Project: 2005 Season,” (with Rhys Townsend and Ece Erdogmus) Anadolu Akdenizi Arkeoloji Haberleri (ANMED) 4 (2006) 99–104.

Hoff, M. and R. Townsend, eds. Rough Cilicia. New Historical and Archaeological Approaches. An International Symposium held at the University of Nebraska, October 2007 (Oxford 2011) forthcoming.

Marten, M.G., ‘Spatial and Temporal Analyses of the Harbor at Antiochia ad Cragum’ (2005) Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations Paper 2715

Turner, C.H., ‘Canons Attributed to the Council of Constantinople, A.D. 381, Together with the Names of the Bishops, from Two Patmos MSS POB’ POG’ ’, The Journal of Theological Studies (1914) M: 72

[1] I’d like to thank Professor Michael Hoff of the University of Nebraska for the permission and freedom to write articles based on the excavations which are due to be published this year, in addition to Associate Professor Birol Can of Ataturk University for his kind permission to publish information on the mosaic and current excavations being undertaken by Ataturk University at Antiochia ad Cragum.

[2] Marten, M.G., ‘Spatial and Temporal Analyses of the Harbor at Antiochia ad Cragum’ (2005) Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations Paper 2715: 5

[3] Marten 2005: 63-68

[4] Marten 2005: 43, 50

[5] Marten2005: 43

[6] Marten 2005: 56, fig. 4.2 – Antiochia ad Cragum Artifact Distribution

[7] University of Nebraska Lincoln Website, Project History – http://antiochia.unl.edu/projecthistory.shtml

[8] Antiocheia (AD 139-161) AE 26 – Marcus Aurelius 100 views Marcus Aurelius as Caesar, 139-161 AD. AE26 (10.40g). ΑΥΡΗΛΙΟC ΚΑΙCΑΡ, head right / ΑΝΤΙΟΧЄΩΝ Τ-ΗC ΠΑΡΑΛΙΟΥ, nude male god holding long scepter, mantle over shoulder. Nice green patina, VF.

[9] Antiocheia (AD 244-249) AE 29 – Philip I58 views Philip I, 244-249 AD. AE29 (13.00g). Laureate draped and cuirassed bust right / ANTIOXЄωN THC ΠAPAΛIOV, eagle on wreath. Very fine; Antiocheia (AD 249-251) AE 26 – Trajan Decius279 viewsTrajan Decius, 249-251 AD. AE26 (7.83g). Laureate, draped, and cuirassed bust right / Eagle standing facing on wreath, head left. Good VF, jade green patina.

[10] “Rough Cilicia Archaeological Project: 2005 Season,” (with Rhys Townsend and Ece Erdogmus) 24. Arastirma Sonuçlari Toplantisi (24th Annual Archaeological Survey Symposium). Turkish Ministry of Culture (Ankara 2007): 231–44.

[11] Project Sponsors include: National Science Foundation, Loeb Classical Library Foundation, Harvard University, Research Council, University of Nebraska, Vice Chancellor for Research, University of Nebraska, College of Fine and Performing Arts, University of Nebraska, Dean’s Office, Clark University

[12] “The Rough Cilicia Archaeological Project: 2005 Season,” (with Rhys Townsend and Ece Erdogmus) Anadolu Akdenizi Arkeoloji Haberleri (ANMED) 4 (2006): 99–104; “Rough Cilicia Archaeological Project: 2005 Season,” (with Rhys Townsend and Ece Erdogmus) 24. Arastirma Sonuçlari Toplantisi (24th Annual Archaeological Survey Symposium). Turkish Ministry of Culture (Ankara 2007): 231–44.

[13] “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2007 Season” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend), 25. Arastirma Sonuçlari Toplantisi (25th Annual Archaeological Survey Symposium). Turkish Ministry of Culture (Ankara 2009): 95-102.

[14] “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2008 Season” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend), 27. Arastirma Sonuçlari Toplantisi (27th Annual Archaeological Survey Symposium).Turkish Ministry of Culture, Ankara 2009 (with R. Townsend and E. Erdogmus): 461-70

[15] “The Antiochia ad Cragum Archaeological Research Project: Northeast Temple 2009 Season” (with E. Erdogmus and R. Townsend), Anadolu Akdenizi Arkeoloji Haberleri (ANMED) 8 (2010): 9-13.

Related articles

- Late Roman mosaic at Antiochia ad Cragum (adrianmurdoch.typepad.com)

- Excavation Projects in Ancient Corinth (greece.greekreporter.com)

- Roman-era mosaic tiles found in Milas (worldbulletin.net)

Macquarie Ancient Languages School – Winter Session

Hello Followers, The Macquarie Ancient Languages School Winter Session is now enrolling for 1-5 July 2013. These intensive courses are open to anyone and everyone, public and students, of all ages and backgrounds. I usually teach the Greek courses but will be in Turkey this year. They are still running though in other capable hands while I am away. 🙂

For the Winter school program you can download it here. Along with the application details. Travel subsidies are available for those coming from further away, we help cater for both national and international attendees.

For all enquiries you can contact:

Jon Dalrymple

Ancient Cultures Research Centre

Department of Ancient History

Macquarie University NSW 2109

Telephone: (02) 9850 9962

Fax: (02) 9850 9001

Email: mals@mq.edu.au

The Macquarie Ancient Languages School, an initiative of the Ancient History Documentary Research Centre, has been running since 1981, offering courses in a wide variety of languages associated with Ancient History and Biblical Studies. Held over two weeks in January and one week in July, the School has branched out from its beginnings in Classical Greek to include classes in Koine Greek, Latin, Egyptian Hieroglyphs, Classical Hebrew, Coptic, Akkadian, Sanskrit and a range of other ancient languages. Some are offered at each school, others on a rotational basis, for example, Aramaic, Hieratic and Old Norse.

There are also opportunities to participate in hands-on courses, working with papyri, inscriptions and coins from the collections in the Museum of Ancient Cultures. New courses are incorporated into the programme on a regular basis. Recent additions include the Linear B Tablets, Latin Inscriptions, the Vindolanda Tablets, and Latin Vulgate Psalms. There are also introductory courses on various topics – for example, Etruscan, Cuneiform and Celtic Languages.

- Are you looking for a challenge in 2013?

- Perhaps you are considering enrolling in a degree programme and would like to include an ancient language?

- Taking part in a Macquarie Ancient Languages School is a great way to ‘test the water’, prior to enrolling in an accredited unit.

Classes in Classical Greek, Koine/New Testament Greek, Classical Hebrew and Egyptian Hieroglyphs are offered at three levels, ranging from Beginners (requiring no prior knowledge) to Advanced level, reading from selected texts.

Classes in other ancient languages are conducted at the Beginners level in January, with follow-on classes in July, subject to student demand. Examples of languages offered in the past include Coptic, Akkadian, Aramaic, Sanskrit, Syriac, Hittite and Sumerian, and more recently, Demotic and Hieratic.

Classes are open to people of all ages (from 16 years) and are suitable for:

- intending students of Greek and other ancient languages in tertiary institutions and theological colleges, and those interested in learning to read the New Testament in Greek

- secondary teachers and students of Ancient History

- those interested in learning more about their heritage, for example, those with Celtic, Greek or Italian ancestry

- those with a general interest in language

- those interested in English literature, in European civilisation, in drama, philosophy, theology, in the ancient world generally, and in the many fields in which ancient literature and thought have been for centuries a powerful influence.

Teaching is in small tutorial groups meeting either in the mornings or afternoons. The timetable is planned to allow students to enrol in more than one subject – for example, a morning class in Classical Hebrew might be followed by a practical session on Greek Papyri in the afternoon. The timing of both Summer and Winter Schools is designed around the Macquarie University calendar, making it possible for currently enrolled students to attend. For those considering an ancient language as part of their degree, such a course is an ideal introduction to the subject, prior to enrolling in an accredited unit. Similarly, both Schools take place in NSW school holidays, so that secondary school students and teachers may attend.

Many of our students come back year after year, not only to enjoy the contact with other like-minded students, but also to brush up on their Greek or other ancient languages, and to continue their fascination with the worlds opened up by the language and literature of these ancient cultures. Their continued attendance is testimony to the enthusiasm generated by the Macquarie Ancient Languages School over the past three decades.