Byzantine Empire

Examples in Archaeology: The Multiple Burial in the Corner of the Hexamilion North of the Roman Bath (Gully Bastion)

When and where the feature was found

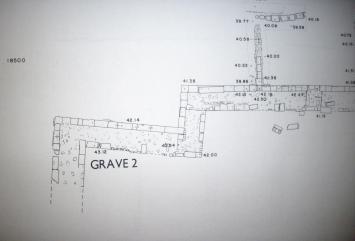

The multiple burial (Grave 2 Gully Bastion) is located in the Corner of the Hexamilion North of the Roman Bath at Isthmia. The grave cut into what is assumed to be ground level at the time of the construction of the Hexamilion wall which is a hard white soil. The grave itself was excavated in the 1970 season and was found under a later kiln or oven.

Gregory, T.E., Isthmia: Vol.5, The Hexamilion and the Fortress (1993)

Topelev = 41.08

Botelev = 40.18

Brief Description

Located in a corner of the Hexamilion wall the Gully Bastion Grave Two has the interior face of the wall forming both the West and the North sides with the North side slightly undercutting the Hexamilion by around 20cm. The sides of the grave are lined with large tiles, these tiles also included in their number one stamped tile[1] and another which being heavily smoke stained indicates that it may have originally been part of the nearby Roman Bath.[2] The interpretation of this tile as formerly of the Roman Bath is also suggested by how the smoke staining does not extend to the corners of the tile where it would have been resting on top of hypocausts.

The grave is actually split into two irregular sections, North and South. These two sections were split by a line of vertical tiles which ran West to East across the grave. Within the north section was found two skeletons with their heads to the west and within the south compartment eight skeletons were uncovered also with their heads to the west. There is some debate to who these individuals were, whether they were part of the garrison assigned to guard or build the Hexamilion or from some other associated part of society.

Underneath the lowest body in the southern section a number of artefacts were found, namely an Athenian glazed lamp fragment which shares much of the characteristics of other lamps found in the Roman Bath (IPL 70-100)[3] which can be dated to the second half of the fourth century after Christ. There is debate over the function of the lamp in the grave. Was it part of some religious ceremony for the deceased or simply just lost or for another reason yet to be thought of? Either way this lamp fragment allows for the best dating of the grave in relation to similar lamps found in the Roman Bath as mentioned previous. Several other items were found in the same area as the lamp fragment including a coarse dark reddish bowl (IPR 70-26) which like the lamp can be dated to the second half of the fourth century.[4] A bronze buckle (IM 70-32) and a bead on a wire (IM 70-54) were also excavated.

Interpretation:

The north side of the grave undercutting the Hexamilion along with the relation between the lamp fragment found in the south section of the grave in relation to lamps found in Roman Bath dating to the fourth century suggest that the grave was contemporary with the construction of the Hexamilion. This is further indicated by how the grave sides are the interior of the wall on two sides. The graves construction can hence be placed either at the time the Hexamilion was being built or slightly after but before the kiln/oven was placed on top.

The position of the skeletons within the grave suggests primarily a Christian burial with the skeleton’s heads to the west. Christian burials of the period were generally orientated East-West with the head to the West end of the grave in order to mirror the layout of the Christian Church and the direction from which Christ is meant to come on judgement day.

References

Gregory, T.E., Isthmia: Vol.5, The Hexamilion and the Fortress (1993), pp.42-45

Notebooks:

Gully Bastion 1970 Vol.2 – pp.47-72 May 1970

Gully Bastion 1970 Vol.3

Wohl ‘Deposit of Lamps’ No. 24

Fraser, P.M., Archaeology in Greece, 1970-71, Archaeological reports, No.17 (1970-71), p.9

Ephesus: A Turkish Pompeii and Tourist Homing Beacon

In my recent adventures in Turkey we were lucky enough to visit the amazing site of Ephesus on the Western coast of the country. This site is a must see and I certainly understand the hype but as an academic a few things struck me which need to be addressed. Namely the lack of accurate information that is actually given by the tour guides we pasted. So here is some accurate information on this awesome site. And remember (I see this everywhere) the tour guides are not always right, do your research before you go.

Before I tell you about the site’s amazing archaeology, let me give you some background. Ephesus was established in the Greek period and was a major city all through to the later Roman periods. In Turkish it is now called Efes (yes like the beer) but the original Greek was Ἔφεσος which is where we take our English transliteration. In its height it was one of the largest cities in the Graeco-Roman world with a population of around 250,000 people in the first century BCE which certainly accounts for the large amount of material on the site. This site is huge!

There are two modern entrances to the site at either end but the main entrance is down at the bottom of the hills in the valley where you are immediately struck by the massive theatre which sits at the end of a long colonnaded street leading to the city’s harbour. To the right of this theatre is the entrance to the main part of the site, the paved streets that are lined with houses, shops, bath houses, toilets, government buildings and of course the famous library of Celsus. If you do get a chance to visit this site then be warned it is easy to miss this path to the main site because of the huge number of tourists that dwell in the shade in that area and block the entrance. It took us three attempts to find it.

The site itself has been inhabited since at least the Neolithic age. Excavations at the mounds in the area have demonstrated this. The habitation appears to be continuous as excavations at the Ayasuluk hill in the 1950s also turned up Bronze age material and a burial ground from the Mycenaean period. Artefacts included ceramics and tools around the ruins of the later site of the basilica of St John which you can still visit today. Hittite sources also tell us that the area held a settlement named Abasa which was in use under the rule of the Ahhiyawans before the Greek migrations took over the area in the 13th and 14th Centuries and established a new settlement. Ephesus was eventually founded as a colony in the 10th century BC. The mythical story of its origins involved King Kadros who was led to the place of Ephesus by the famous Delphic oracle. Though there are several other origin stories including those discussed by Pausanias and Strabo concerning the queen of the Amazons, Ephos, as a founder.

Over the centuries the city saw many conflicts including attacks by the Cimmerians and the Lysians. The city though continued to prosper and became the base of and producing a number of significant historical figures. For instance, the poets Cllainus and Hipponax, the philosopher Heraclitus and the physicians Soranus and Rufus whos writings we still have today. The Classical period saw more conflicts with the Ionian revolt and the Peloponnesian war, in which Ephesus originally allied with Athens and then switched to Sparta in the later stages. During this time though it continued its upward climb and produced even great female artists like Timarate who is mentioned in Pliny the Elder as the painter who produced a fabulous representation of the goddess Diana.

Alexander the Great liberated the site from Persian rule at the end of the Classical period and is said to have entered Ephesus in triumph. He even proposed to rebuild the Temple of Artemis which had been burned down in previous conflicts. After the death of Alexander though turmoil retuned under the rule of his general Lysimachus but after his eventual death, Ephesus became part of the Seleucis Empire and then was governed under Egyptian rule from the late 2nd century BC. Ephesus eventually became a part of the Roman Republic. All these influences and changes certainly led to a diverse site with establishments of buildings and institutions in all these periods. And the diversity continued as the site continued to function as part of the Byzantine era when Constantine I rebuilt much of the city and built a new public bath after the conflicts of the Roman period. Unfortunately though Ephesus has one enemy which they couldn’t defeat, the area is often troubled by earthquakes and one in 614 partially destroyed the city again.

Considering all the conflicts it has seen, all the people and leaders, it is both understandable and surprising that so much is left of this site. And so now we have got through the date part and you have some background information let me tell you about the site itself from an archaeologist’s perspective.

This site really is the archaeologist’s dream, I would happily dig on this site for years and years. You can see obviously that much of the site has been reconstructed which is fabulous and appears to be very well done. There are certain areas though that obviously stand out. The first of these being Celsus’ library. Apart from witnessing teen girls posing doing duck faces next to a status of wisdom (I’m so glad these statues are replicas because i can see the real ones throwing themselves out of their niches in horror), this is by far the most magnificent part of the site. It is truly a shame that the majority of people who visit the site do not know much about it. The library was built at the beginning of the second century CE for Julius Celsus Polemaeanus, who was the governor of the province, by his son Galius Julius Aquila and was actually built as a tomb rather than specifically a library. The façade is all that really remains today but once upon a time this building is thought to have been able to hold over 12,000 scrolls. As such it is thought to have once been the third richest library of the ancient world following the libraries of Alexandria and Pergamum. The library is an amazing building and to someone who understands its significance it really does stand for the virtues that are inscribed on its walls including knowledge, wisdom, intelligence and valour. Just ignore the posing tourists who are updating their Facebook profile pictures.

While it appears that most people go round, look at the theatre and the library and then have an ice cream, this site has some truly amazing parts that you only really appreciate if you have researched them before hand or know about archaeology. The agora for instance, which was built in the Roman period played an important role as a social and political meeting place but the archaeology shows that the area was in use far before these functions. Excavations have brought to light graves from the seventh and sixth centuries BCE including an archaic sarcophagus made from terracotta. There is also a well preserved water reservoir in the corner of the ahora which demonstrates just how technically accomplished these people were. Its water was supplied by the Pollio Aqueduct which supplied the whole city from 5km away. The agora also contained stoas and a temple with dedications to the cult of Isis and evidence of rebuilding in different periods indicative of the turmoil the city suffered.

The emphasis on the large theatre is well justified but the odeon is also a significant area. Unfortunately it was while looking at this I heard a tour guide tell tourists incorrectly that they used to have gladiator fights here…It’s an odeon, it is tiny, just no. First of all this area was used as a Bouletarion (a meeting place) for meetings of the Bouleia (council) and members of the Demos. It was also used for performances. The building is impressive though fairly small in size and demonstrates the wealth of its benefactors. It was orders by Publicus Vedius Antonius and his wife in the second century.

Among other impressive areas of the site is the well reconstructed fountain of Trajan built at the start of the second century CE. It’s columns and pediments really give you an idea of what it would have looked like in its prime. It is an excellent tool for giving the visitors more of an idea of the ancient city and its statues are now in the museum. It is just a real shame that the Ephesus Archaeology Museum is shut for renovations for an entire year!

There is so so much to this site it can not be written down. I could tell you about the temples, the gateways, fountains, houses, whole city but you have to visit it to appreciate everything. Either way I encourage that you look up this site and read more because this really was a site to remember.

Related articles

- The Turquoise Riviera – Part II: Ephesus (greetingsfromacrossthemiles.wordpress.com)

- Ephesus vs Hierapolis: Seeking The Secret Amphitheater (katrinkaabroad.com)

- Ephesus (comesailwithmesas13.wordpress.com)

- Ephesus (sjgoodwright.wordpress.com)

- Ephesus Tours Turkey (sammyinturkey.wordpress.com)

- The ancient ruins of Ephesus (workasylum.wordpress.com)

- Impressions of Ephesus (socyberty.com)

- An ‘Unforgettable’ Evening At Ephesus, As Silver Spirit Docks In Kusadasi (avidcruiser.com)

- Ephesus (carrierosslynne.wordpress.com)

- Ephesus (laureneagleson.wordpress.com)

Philology: Introduction to the Significance of Language Analysis

When you first enter an ancient history or archaeology degree you are introduced to several sets of material evidence. Notably, the archaeology, material evidence, and philological evidence. But the philological side is more often than not rarely mentioned again. This is quite a shame considering some of the most interesting and revealing information comes from the ancient written sources. People generally fall into the trap of ignoring the writing in favour of the archaeology and artefacts and frankly you can’t really blame them because humans are naturally attracted to pretty visual things. I see this every day with the likes and shares on my Facebook page. But philology is all important too and if students can learn even a little about ancient writing and textual criticism, a whole new side to history and analysis opens up to them as it should.

Philology is derived from the Greek terms φίλος (love) and λόγος (word, reason) and literally means a ‘love of words’. It is the study of language in literary sources and is a combination of literary studies, history and linguistics. Philology is generally associated with Greek and Classical Latin, in which it is termed philologia. The study of philology originated in European Renaissance Humanism in regards to Classical Philology but this has since been combined to include in its definition the study of both European and non-European languages. The idea of philology has been carried through the Greek and Latin literature into the English language around the sixteenth century through the French term philologie meaning also a ‘love of literature’ from the same word roots.

Generally philology has a focus on historical development. It helps establish the authenticity of literary texts and their original form and with this the determination of their meaning. It is a branch of knowledge that deals with the structure, historical development and relationships of a language or languages. This makes it all the more significant to study as language is one of the main building blocks of civilisation.

There are several branches of philological studies that can also be undertaken:

Comparative philology is a branch of philology which analyses the relationship or correspondences between languages. For instance, the commonalities between Latin and Etruscan or further flung languages of Asian or African provinces. It uses pre-determined techniques to discover whether languages hold common ancestors or influences. It uses comparison of grammar and spelling which was first deemed useful in the 19th century and has developed ever since. The study of comparative philology was originally defined by Sir William Jones‘ discovery in 1786 that Sanskrit was related to Greek and German as well as Latin.

Cognitive philology studies written and oral texts in consideration of the human mental processes. It uses science to compare the results of research using psychological and artificial systems.

Decipherment is another branch of philology which looks at resurrecting dead languages and previously unread texts such as done and achieved by Jean-Francois Champollion in the decipherment of Hieroglyphs with the use of the Rosetta Stone. And more recently by Michael Ventris in the decipherment of Linear B. Decipherment would be key to the understanding of still little understood languages such as Linear A. Decipherment uses known languages, grammatical tools and vocabulary to find and apply comparisons within an unread text. By doing so more of the text can be read gradually as similarities and grammatical forms become better understood. The remaining text can then be filled in through further comparison, analysis, and elimination of incorrect solutions.

Textual philology editing is yet another branch of philology with includes the study of texts and their history in a sense including textual criticism. This branch was created in relation to the long traditions of Biblical studies; in particular with the variations of manuscripts. It looks at the authorship, date and provenance of the text to place it in its historical context and to produce ‘critical editions’ of the texts.

Significant Examples:

The importance of philology is exhibited in its use and achievements. Without philology the bible translation would be even more wrong, trust me read it in the original Greek. We would not be able to translate hieroglyphs, Linear B, Linear A, Sanskrit, any ancient language. Our entire written past would be blank, we would not have the information we have now on mathematics, social structure, philosophy, science, medicine, civilisation, transport, engineering, marketing, accounting, well anything really, knowledge would not have been rediscovered or passed on without the ability to study texts and language. Understand the love of words.

Related articles

- The unsung heroine who helped decode Crete’s ancient script (bbc.co.uk)

- Rediscovering Philology (sites.tufts.edu)

- The Open Philology Project and Humboldt Chair of Digital Humanities at Leipzig (sites.tufts.edu)

- Genes and Languages: Not So Strange Bedfellows? (23andme.com)

- Bavinck on Comparative Religion and Comparative Philology (calvinistinternational.com)

- How to Teach yourself Ancient (and Modern) Languages (graecomuse.wordpress.com)

- Welcome to GraecoMuse (graecomuse.wordpress.com)

- Alice Kober: Unsung heroine who helped decode Linear B (adafruit.com)

- The Unsolved Mysteries of the World (secretsofthefed.com)

- Macquarie Ancient Languages School – Winter Session (graecomuse.wordpress.com)

Koenig wrote that “Religious tolerance is something we should all practice; however, there has been more persecution and atrocities committed in the name of religion and religious freedom than anything else.” This post will look at the persecution of Christians through Eusebius’ Historica Ecclesiastica and other primary and secondary sources.

Koenig wrote that “Religious tolerance is something we should all practice; however, there has been more persecution and atrocities committed in the name of religion and religious freedom than anything else.” This post will look at the persecution of Christians through Eusebius’ Historica Ecclesiastica and other primary and secondary sources.