An Introduction to Ajax the Polis Hero

In Sophocles’ ‘Ajax’, Ajax possesses many qualities of the heroic ideal and some less desirable qualities as a hero. Ajax is mostly known for his physical strength and military prowess as recounted by Odysseus in Sophocles after Ajax’s death. Wilson assesses Sophocles’ Ajax as courageous and self reliant which can also be attributed to the heroic ideal, it can be evaluated from Sophocles that Ajax was a man of few words. It can be observed from ‘Ajax’ 670-83 that though blunt in speech, Ajax had certain “clarity of insight” which also asserts wisdom of sorts that can be attributed to Ajax as a hero; he can be seen as the Sophoclean hero who has gained wisdom through experience. However, Ajax can also be assesses as proud and boastful, also he becomes angry and unpredictable when he loses Achilles’ armour which are much less desirable qualities.

In Sophocles’ ‘Ajax’, Ajax possesses many qualities of the heroic ideal and some less desirable qualities as a hero. Ajax is mostly known for his physical strength and military prowess as recounted by Odysseus in Sophocles after Ajax’s death. Wilson assesses Sophocles’ Ajax as courageous and self reliant which can also be attributed to the heroic ideal, it can be evaluated from Sophocles that Ajax was a man of few words. It can be observed from ‘Ajax’ 670-83 that though blunt in speech, Ajax had certain “clarity of insight” which also asserts wisdom of sorts that can be attributed to Ajax as a hero; he can be seen as the Sophoclean hero who has gained wisdom through experience. However, Ajax can also be assesses as proud and boastful, also he becomes angry and unpredictable when he loses Achilles’ armour which are much less desirable qualities.

In order to assess Ajax’s feelings we must look at the definitions of shame and guilt. The OED defines shame as “a feeling of humiliation or distress caused by awareness of wrong behaviour, loss or respect or esteem” and guilt as the recognition of wrongdoing. An assessment of Ajax’s behaviour does indicate that he does feel shame and guilt in Sophocles, as agreed by Platzner and Harris. However, Wilson asserts that Ajax thinks primarily of himself and maintaining heroic status. This suggests that it may not be shame and guilt that Ajax is feeling in the sense of feeling sorry for his actions, but arrogance in that he is first concerned with his image as a hero and his loss of honour, instead of the damage he did. Ajax may have felt shame and guilt but this seems to be primarily concerning his loss of honour and heroic reputation.

Ajax can be seen as similar to Homer’s Achilles. Homer represents Achilles as larger that life, a superman type figure; this can also be said of Sophocles’ Ajax. Pausanias describes how angry Ajax became at being dishonoured concerning Achilles’ armour; this concern for personal honour is also seen in Homer’s Achilles in his feeling relating to Agamemnon. This suggests that both characters possess a great sense of glory and honour as their first and foremost priorities. Both heroes also seem to have a great loyalty to one another as seen in black figure pottery of them playing games together. Another similarity is the idea of invulnerability as displayed in some texts. There are also differences between the two characters. Ajax in Sophocles refuses the gods for example where as Achilles has a sense of piety, Achilles unlike Ajax, choice the more honourable death.

Plato explains the importance of every community to have a hero; Ajax can be assessed as a hero of the polis in the manner of him being the local hero and of family ancestry in both Salamis and Athens. An assessment of these traits in relation to the importance before expressed by Plato, Ajax became a polis hero. Hesiod explains how the Heroes of the Polis defended it. This suggests that Ajax was a hero for the Polis because he would defend it, however, this can be seen as an example of mutual obligation between the people and the hero, Ajax was interested in honour, by honouring him, the people of the polis were thought to be protected. Ajax is a polis hero as he is a representation of defence and power that would help to protect it, Ajax’s strength and fighting ability is seen in Attic red figure pottery.

Bibliography

Adams, S.M, The “Ajax” of Sophocles, Phoenix, Vol 9 no 3 (1955) pp. 93-110

Evelyn, H.G, Hesiod, Works and Days, University Press, London, William Heinemann Ltd.159-169

Green, P. A Concise History of Ancient Greece, Thames and Hudson, London, pp. 44-47

Harris, S.L. and Platzner, G. (2001), Classical Mythology, Images and Insights, Third Edition, Mayfield Publishing, California, pp. 797

Homer, Iliad, Translated by A.T. Murray, 1924, Book 1

Jebb R.C, Sophocles 7, Cambridge (1907) xii

Kerenyi, C. (1997), The Heroes of the Greeks, Thames and Hudson, London, pp. 319-330

Knox, B.M.W, The Ajax of Sophocles, Harvard studies in classical philology (1961), Vol 65 pp.1-37

Millard A, Ancient Greece, Usborne Publishing, London, pp. 36

Oxford English Dictionary

Pausanias 1.35.3, Translated by W.H.S. Jones and H.A. Oremrod, Heinemann, London

R.G. Bury, Plato’s Laws, Harvard University Press, London, William Heinemann Ltd. 738d

Sophocles, Ajax, Translated by R.C. Trevelyan London, G. Allen and Unwin (1919)

Tzetze, On Lycrphon 455-461

Wilson J.P, The Hero and the City, University of Michigan Press, America, pp.60, 176, 179-185

Studying for History Exams and in General

Studying for History Exams and in General.

It’s almost exam period again. So see this previous post for some techniques and tips for students everywhere.

And a funny video.

Where is Archaeology Blogging Going? #BlogArch

This month is the last month of the Blogging Archaeology Carnival that you may have seen participation in on other blogs and websites as well as GraecoMuse. This month we are looking at where we plan to take our blogging or where we would like to go.

“…where are you/we going with blogging or would you it like to go? I leave it up to you to choose between reflecting on you and your blog personally or all of archaeology blogging/bloggers or both. Tells us your goals for blogging. Or if you have none why that is? Tell us the direction that you hope blogging takes in archaeology.”

So where am I going with blogging about archaeology and ancient history? Well personally, as I’ve already mentioned in some of my previous posts, this to me is about productive procrastination. But I have realised that it is more than that and there are certainly things I’d like to achieve. One thing you often find with academics is a vast negativity about careers and research which can be very overwhelming especially for young academics or those who wish to expand into the field for any reason. I would like to show that there are those out there who are positive, who are willing to help and promote learning for all in a way that is fun and inspiring. This negativity is often called realism but seriously archaeology and academia is different for everyone and if you love it enough you will go far. You just need to be proactive. And if you don’t end up in academia that’s totally fine, you can still be part of this wonderful thing called history and do things that interest you and learn all that you want.

So in brief I what to promote a more positive view of history and archaeology which it deserves.

So in brief I what to promote a more positive view of history and archaeology which it deserves.

I also realised that I want to help those who are a little less knowledgeable but want to be knowledgeable. To make resources more available to those outside or academia and students themselves. Especially in the US, I have found that students simply don’t know and haven’t been told how to find information. This blog has become more than just random posts and includes access to such things which people can access really easily.

So access to resources for all! On the blog, on facebook, on twitter, everywhere!

Frankly though my main goal is a bit selfish. I have fun researching things and blogging is just fun. But in the end I would like blogging to continue what it has already started, making archaeology and ancient history more inclusive and more available to everyone. So many people are not aware of the value of archaeology and history and it’s about time they were. And I think bloggers and others are finally achieving this. For instance it is through people like us that word is got out about bad archaeological practices. For instance the horrible National Geographic Show Nazi Diggers which got pulled before it ever aired because of PUBLIC and professional outcries.

Archaeology and history are amazing. I also want to show that media dramatizations of events and the like are completely unnecessary. It seems the media these days really does thing its audience is bloody stupid and need all the stupid dramatizations and dramatic music and the like. History doesn’t need this, we don’t need this, their audiences don’t need this. Let history speak for itself. It is dramatic, it is amazing.

Hopefully with the rise of blogging in archaeology and ancient history, someday people will realise it.

http://dougsarchaeology.wordpress.com/2013/11/05/blogging-archaeology/

Zeus and his Siblings: An Introduction

We hear so much about Zeus and the Olympic Gods but who were they? It worries me sometimes when an archaeology student doesn’t know the basics so let’s begin! Hesiod explains that Zeus’s parents were Cronus and Rhea and his siblings included Hades, Poseidon, Hera, Hestia and Demeter. Hesiod accounts that Zeus fathered seven lesser gods, but only two of these were with his wife/sister’s Hera.1 These children were Ares and Hephaestos, Athene, Artemis and Apollo, Hermes and Aphrodite. 2 Though accounts made by Hesiod are generally agreed on by Homer, Homer’s works do indicate that he believed that all gods originated from the Ocean. Gantz explains that Homer implicates that Oceanos and Tethys were the actual parents of Zeus. 3

We hear so much about Zeus and the Olympic Gods but who were they? It worries me sometimes when an archaeology student doesn’t know the basics so let’s begin! Hesiod explains that Zeus’s parents were Cronus and Rhea and his siblings included Hades, Poseidon, Hera, Hestia and Demeter. Hesiod accounts that Zeus fathered seven lesser gods, but only two of these were with his wife/sister’s Hera.1 These children were Ares and Hephaestos, Athene, Artemis and Apollo, Hermes and Aphrodite. 2 Though accounts made by Hesiod are generally agreed on by Homer, Homer’s works do indicate that he believed that all gods originated from the Ocean. Gantz explains that Homer implicates that Oceanos and Tethys were the actual parents of Zeus. 3

Platzner and Harris explain that Zeus and his offspring did represent aspects of human beings so were anthropomorphic. Zeus represents the complexity of human sexuality/lust.4 Grimal also links Zeus to mortals with the idea of being subject to fate. Zeus’s offspring can also be seen as displaying anthropomorphic qualities. Aphrodite was the goddess of love, love being at the heart of all humans and something that all desire.5 All the gods maintained human characteristics, such as Artemis’ wildness and anger, and Athene’s strength and warrior like qualities.6 Though these gods represent the world around us such as the ocean and earth, they also include human characteristics which govern their actions. So to a fair extent, Zeus and his offspring are anthropomorphic deities.

Kerenyi assesses that Zeus’s main attributes and Functions include his place as a supreme being, as father of the gods. 7 Zeus’s defeat of the Titans illustrates military prowess, strength and he is seen as a divine warrior. 8 Platzner and Harris assert that Zeus is a representation of the complexity of human sexuality in his lust, saying that “modern mythologists tallied no fewer than 115 different objects of Zeus’s affections”. 9 Zeus also was the “distributor of good and evil” 10, meaning that he has the function of maintaining the balance of the universe. He is also attributed to being the divine patron of the Olympic Games.

The older Olympian gods are still seen as creator gods and are generally related to universal ideas. They are more firmly intertwined with the universe as a whole and have greater and broader areas of influence. For instance, Hesiod describes Zeus as maintainer of balance in the universe, as the overseer of all that is good and evil. 11 Hera retains the creative power of her parents, an attribute which controls life itself. Poseidon is seen as the king of the sea, the ocean being a powerful force of nature. The younger Olympian god’s attributes are more specific. An assessment of Homer and Hesiod’s works suggest that these gods were more linked to certain aspects of humanity. 12 For instance, Artemis as the goddess of midwifery and childbirth and Apollo being the communicator of the God’s will to humanity. 13

The nature myth theory acts as an explanation for the creation of life as the ancient Greeks knew it. An assessment of this theory suggests that the functions of the Greek Pantheon were an extension of this explanation, further creating reason behind aspects of life by providing personifications of the world and of human characteristics. The theory explains the attributes and functions of the Pantheon to a great extent as it is the base from which the ideas of life and creation emerge which are reflected in the Pantheon’s traits.

- Hesiod, Theogony and Works and Days , Hesiod; West, M. L. , (1988)

- Harris, S.L. and Platzner, G., Classical Mythology, Images and Insights, Fourth Edition, (California, 2004), p. 178

- Gantz, T., “The Olympians” in Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources (London, 1993)

- Harris, S.L. and Platzner, G., op.cit., p.182

- Grimal, P., Dictionary of Classical Mythology (London, 1991), p. 47

- ibid., p.60, 66

- Kerenyi, C. (1997), The Gods Of The Greeks (London, 1961), p. 91

- Hesiod, op.cit., Book 1

- Harris, S.L. and Platzner, G., op.cit., p.182

- Grimal, P., op.cit., p. 454

- Hesiod, op.cit, Book 1

- Homer, Iliad, (Translated by A.T. Murray, 1924)

- Harris, S.L. and Platzner, G., op.cit., 194

Bibliography

Gantz, T., “The Olympians” in Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources (London, 1993), pp. 57-119 .

Grimal, P., Dictionary of Classical Mythology (London, 1991), pp. 47, 60, 66, 453-456

Harris, S.L. and Platzner, G., Classical Mythology, Images and Insights, Fourth Edition, (California, 2004), p. 178, pp.177-198

Hesiod, Theogony and Works and Days , Hesiod; West, M. L. , (1988)

Homer, Iliad, (Translated by A.T. Murray, 1924), Book 1

Homer, Odyssey (translated by A.T.Murray, 1919)

Kerenyi, C. (1997), The Gods Of The Greeks (London, 1961) , pp. 91-116

Kirk, G. S., The Nature of Greek Myths (London, 1988), pp. 113-145

Pinsent, J. (1969), Myths and Legend Of Ancient Greece (London), pp. 148-152

Examples in Archaeology: The Multiple Burial in the Corner of the Hexamilion North of the Roman Bath (Gully Bastion)

When and where the feature was found

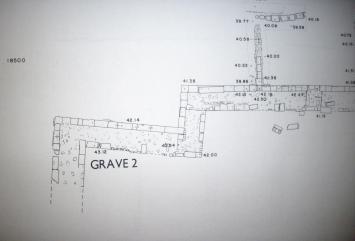

The multiple burial (Grave 2 Gully Bastion) is located in the Corner of the Hexamilion North of the Roman Bath at Isthmia. The grave cut into what is assumed to be ground level at the time of the construction of the Hexamilion wall which is a hard white soil. The grave itself was excavated in the 1970 season and was found under a later kiln or oven.

Gregory, T.E., Isthmia: Vol.5, The Hexamilion and the Fortress (1993)

Topelev = 41.08

Botelev = 40.18

Brief Description

Located in a corner of the Hexamilion wall the Gully Bastion Grave Two has the interior face of the wall forming both the West and the North sides with the North side slightly undercutting the Hexamilion by around 20cm. The sides of the grave are lined with large tiles, these tiles also included in their number one stamped tile[1] and another which being heavily smoke stained indicates that it may have originally been part of the nearby Roman Bath.[2] The interpretation of this tile as formerly of the Roman Bath is also suggested by how the smoke staining does not extend to the corners of the tile where it would have been resting on top of hypocausts.

The grave is actually split into two irregular sections, North and South. These two sections were split by a line of vertical tiles which ran West to East across the grave. Within the north section was found two skeletons with their heads to the west and within the south compartment eight skeletons were uncovered also with their heads to the west. There is some debate to who these individuals were, whether they were part of the garrison assigned to guard or build the Hexamilion or from some other associated part of society.

Underneath the lowest body in the southern section a number of artefacts were found, namely an Athenian glazed lamp fragment which shares much of the characteristics of other lamps found in the Roman Bath (IPL 70-100)[3] which can be dated to the second half of the fourth century after Christ. There is debate over the function of the lamp in the grave. Was it part of some religious ceremony for the deceased or simply just lost or for another reason yet to be thought of? Either way this lamp fragment allows for the best dating of the grave in relation to similar lamps found in the Roman Bath as mentioned previous. Several other items were found in the same area as the lamp fragment including a coarse dark reddish bowl (IPR 70-26) which like the lamp can be dated to the second half of the fourth century.[4] A bronze buckle (IM 70-32) and a bead on a wire (IM 70-54) were also excavated.

Interpretation:

The north side of the grave undercutting the Hexamilion along with the relation between the lamp fragment found in the south section of the grave in relation to lamps found in Roman Bath dating to the fourth century suggest that the grave was contemporary with the construction of the Hexamilion. This is further indicated by how the grave sides are the interior of the wall on two sides. The graves construction can hence be placed either at the time the Hexamilion was being built or slightly after but before the kiln/oven was placed on top.

The position of the skeletons within the grave suggests primarily a Christian burial with the skeleton’s heads to the west. Christian burials of the period were generally orientated East-West with the head to the West end of the grave in order to mirror the layout of the Christian Church and the direction from which Christ is meant to come on judgement day.

References

Gregory, T.E., Isthmia: Vol.5, The Hexamilion and the Fortress (1993), pp.42-45

Notebooks:

Gully Bastion 1970 Vol.2 – pp.47-72 May 1970

Gully Bastion 1970 Vol.3

Wohl ‘Deposit of Lamps’ No. 24

Fraser, P.M., Archaeology in Greece, 1970-71, Archaeological reports, No.17 (1970-71), p.9